It's the first day of Spring-hopefully Spring is coming soon! To celebrate, here's a special So You Want to Read Middle Grade post all about natural magic.

Julia Mary Gibson’s novel Copper Magic has grandmothers in it, and a girl who believes she needs magic. Visit juliamarygibson.com to find out more, or follow her on Twitter @juliamarygibson.

NATURAL MAGIC AND THE GRANDMOTHERS

Growing up, my summers were spent in the woods. Our woods weren’t very wild (no bears, no way of getting lost), but there were plenty of fern shadows and shafts of magical sunlight and mossy places that my grandmother said fairies might visit if we left a crumb of sponge cake for them. To me, magic lived in the wind and tangled roots and completely existed. And so my favorite books were about feasible magic, believable magic, the magic of natural law. Of course there could be borrowers like Arrietty Clock beneath our floor. Of course there could be a way into Narnia if one happened to stumble into the right wardrobe.

Maybe because my own grandmother was a gatherer of wild plants with ESP who claimed familiarity with mystical realms, I resonated with the powerful magical females featured in stories about natural magic. Too often in fairy tales, the ancient crone is a destroyer, an eater of children, a feared outcast. Baba Yaga thrilled me, but I got solace and affirmation from the stories where the old lady wisdomkeeper is a conduit to animals, elements, and the departed ancestors.

Some of these books are mainstays, read and reread tens of times as an alienated teenager and into adulthood. Others came into my life more recently. Most of them can be enjoyed by anyone over eight or ten.

The Mary Poppins books by P.L. Travers.

Mary Poppins is a world renewal practitioner who maintains relationships with various sky beings – birds, stars, the Sun. She may look young, but she’s an ageless confederate of the cosmic crones who keep the universe in order: the Bird Woman ministering to the feathered ones, Mrs. Corry keeping plenty of stars in the sky, the Balloon Woman reminding us to know ourselves.

The Princess and the Goblin by George MacDonald.

There are twisted, thwarted beings in the world like goblins, and there are protectors, guides, and healers like the princess Irene’s grandmother, ancient and ageless, with her rose-scented fire and her messenger pigeons. The princess Irene and the miner Curdie are courageous and steadfast like the fairy-tale characters that they are, but they have human weaknesses too. The goblins are both funny and scary, and it stands to reason that they exist – why wouldn’t beings become grotesque after generations underground in the darkness of a mine?

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

Nature is the fixer and unifier in this much-adapted classic. Unloved Mary and Colin create their own magical belief system and healing modality, with the assistance of animal steward Dickon. Dickon’s mother, Susan Sowerby, is the grandmother figure. Though she’s not technically a crone, her magically-numbered twelve children and elemental wisdom qualify her as a stand-in. Magic is in the bracing Yorkshire air, in Mrs. Sowerby’s nourishing buns and milk, in the unfurling leaves of the hidden garden, and in Mary’s brash honesty.

“The Cat that Walked by Himself,” from Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories.

One of the many great things about Kipling’s mythic creation stories is that they’re enjoyable at any age. The language is rich, the unfolding of events is masterful, the characters are simple yet complex. In this tale, the Woman makes the First Singing Magic in the world to tame animals and the slovenly Man. Only the Cat keeps some of his wildness, but he and the Woman both win the contest between them.

Gwinna by Barbara Helen Berger.

This is longer and more complicated than Berger’s wondrous picture books, but in the same transcendent vein. Gwinna is given to a childless couple by the Grandmother of the Owls. When Gwinna sprouts wings, her human foster mother binds them, but Gwinna is tasked with finding a lost song and uses her wings and the music well. Berger’s illustrations are as luminous as the story.

The Birchbark House; The Game of Silence; The Porcupine Year; Chickadee by Louise Erdrich.

Erdrich always leaves me breathless. Her writing for children is only very slightly less intricate and meaty than her books for grownup readers, and in this series she deftly braids family conflict, political and social upheaval, the quest for life purpose, adventure, tragedy, backstory, and cosmology with her trademark lyricism and humor. Young Omakayas is much like Laura in The Little House series – inquisitive, observant, capable - except she’s Anishinabe, not a white settler girl. Seven in the first book and a mother in the fourth, Omakayas is in relationship with earth bears and bear spirits. She learns healing and ceremonial arts from her grandmother Nokomis as the family is challenged by disease and dislocation. She has a second grandmotherly relationship, too – the venerable hunter and trapper Old Tallow, the shadow/yang side of Nokomis.

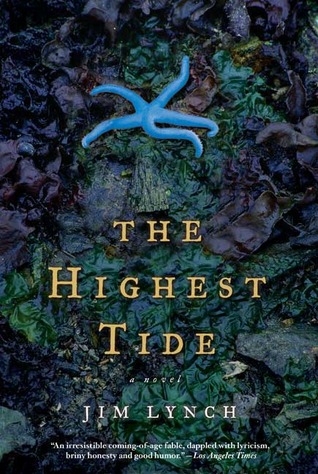

The Highest Tide by Jim Lynch.

Thirteen-year-old Miles is a Rachel Carson devotee and knows more than most people about the sea and its organisms. His findings of rare wonders might have a scientific explanation or might be messages from the deep. Miles’ compulsive beachcombing and knowledge-gathering is the way he contends with his rifting parents and his anguished crush on his compellingly messed-up former babysitter, a singer in a punkish band. The grandmother archetype is Miles’ crotchety neighbor, a self-proclaimed psychic who is rarely right except when it matters.

Comments

Post a Comment

I love hearing from other readers! Share your thoughts and chime in!